The hacks that can help to keep your home warmer

Heat can escape from buildings in a number of ways, but there are some evidence-based, low-cost things you can do to help stay warm.

Pope tried wrapping up as best she could but was still miserably cold. So she called her local authority. They were soon on site with draught blockers and foil backing for her six radiators, the idea being that these reflect heat back into the room rather than letting it escape through the external walls.

“It was just much warmer in here, you couldn’t really feel the draught,” says Pope. “It’s like the heat was being kept in.”

She’s not sure how much the temperature indoors changed, exactly, but she can feel the difference. Her experience suggests that a few simple adjustments to the fabric of a building can boost the warmth inside, especially during cold snaps. Social media is awash with pithy videos outlining tips like these and many more.

However, there’s relatively little scientific data about the efficacy of such measures, to help people choose one over another. Plus, some frequently mentioned ideas – such as heating a room with candles – could be dangerous. Ultimately, in colder climates, it is not advisable to try and do without a heating system in the winter, though you can improve said system’s performance slightly.

Energy poverty is a growing problem in many nations, including the UK – where nearly 5,000 excess deaths caused by cold homes are estimated to have occurred last winter, according to the End Fuel Poverty Coalition. That is a rise of nearly 50% on the previous winter. In the US, the Energy Information Administration says that 27% of households reported energy insecurity – amounting to around 34 million homes.

Here’s what you need to know about budget heating hacks, their potential to save you money – and also their limitations.

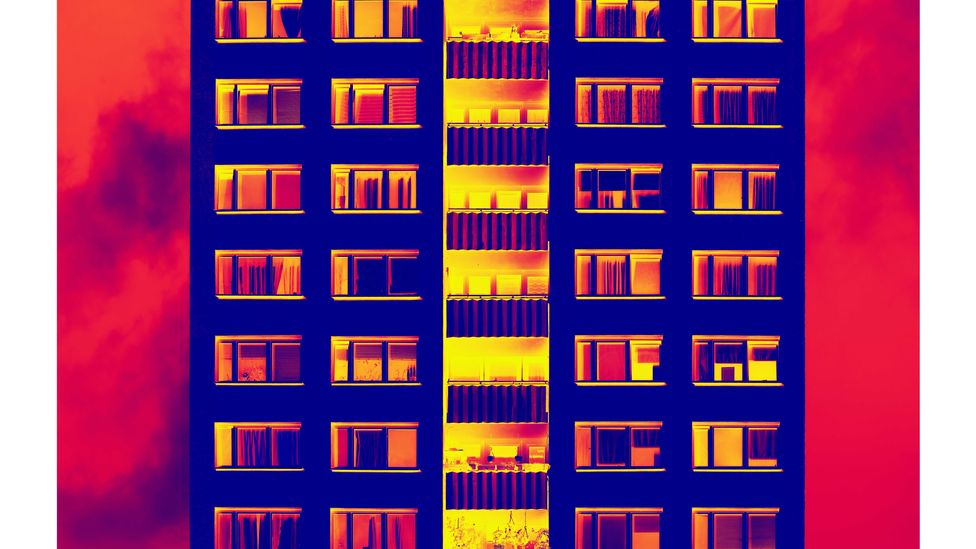

Heat escapes from windows, doors, cracks and other poorly insulated points of many houses (Credit: Getty Images)

“It was a bit of a blank, there wasn’t enough out there about some of these cheaper or free things,” says Katy King, deputy director of sustainable future at Nesta, a UK innovation agency. Last year, Nesta published the estimated savings, in kilowatt hours, that people could achieve by doing things such as applying foil backing to radiators or adding secondary glazing film to their windows.

The figures, based on the expected change to a typical British household’s energy consumption, suggest that reducing the flow temperature – the temperature of water sent to radiators – of a gas combi boiler to 60C (140F) would save £43 ($55) per year. This saving increases if you can turn the flow temperature down even further, says King. Secondary glazing film could also save around £40 ($51) in most homes. These figures reflect the cost of energy as it was in the UK in autumn 2023, although the US Department of Energy estimates that heat passing through windows accounts for about 25-30% of the energy used to heat and cool buildings.

Foil backing for radiators, however, won’t save you as much, according to Nesta’s research and this only works on externally insulated walls in homes with gas- or oil-based heating. However, reducing draughts can be very impactful.

Turning your thermostat down from 20C to 19C (68F to 66F) was estimated to save in excess of £100 ($127) and wrapping up warm instead of relying on your heating system too much can also cut costs over a year. Altogether, the research indicates that free and low cost measures can save several hundred pounds across a year, if combined.

There are plenty of other options too. Turn your radiator thermostatic valves down to between 2 and 3 to achieve roughly 18C (64F), the recommended minimum healthy indoor temperature, for example. And bleed water-filled radiators to remove a build-up of air inside them and improve their heat output when your boiler is running.

The energy crisis in recent years has put many households into fuel poverty (Credit: Getty Images)

King mentions another additional measure not specifically highlighted in the research published by Nesta: reduced-flow shower heads. These will save money by reducing the amount of heating required for a shower and also the volume of water used, if you live in an area where water is metered. For those who do pay for water, this tactic could save around £70 ($89) annually.

It’s also worth thinking about how long you spend in the shower, says Elliot Clark, fuel poverty advisor at the Centre for Sustainable Energy. Especially if you have an electric shower. At current average UK electricity prices, a 10-minute hot shower can cost around 50p (64 cents). That’s not a huge amount on its own, but multiply it by three people and 365 days a year, for example, and it adds up to nearly £550 ($700). By sticking to a four-minute shower you can cut this cost by more than half, Clark says.

Jo Alsop at The Heating Hub, an independent advisory service, emphasises cracking down on draughts. She had an open fireplace in her own living room removed, to great results.

“It transformed my sitting room – it wasn’t sucking all of the warm air out of the house,” she says.

Clark suggests blocking up holes around pipes in external walls or other areas where the brickwork isn’t as well-sealed as it should be. However, it’s important not to block up ventilation bricks or extractor fan outlets.

Thick curtains, draught excluders under doors or in letterboxes can all help, too. Rose Chard, Fair Future Programme Lead at Energy Systems Catapult, a non-profit, says even a small increase in temperature can change lives: “Just one or two degrees and you can see a reduction in respiratory problems or mental health issues. I don’t think that should be underestimated.”

But it is problematic to rely on budget measures too heavily. Often, people use the phrase “heat the person not the room” to emphasise keeping one’s body warm with thermal clothing and electric blankets, for instance, at a lower overall cost. The potential pitfall with this is, if your room gets very cold, then you will still be breathing in cold air, which is potentially harmful, explains Chard: “There can be an impact on respiratory symptoms.”

Plus, cold walls and glazing are magnets for condensation and, therefore, mould. Black mould can be life-threatening and is difficult to eradicate once it establishes itself in a property.

“We want to put people in a situation where they can afford to use their heating,” says Aimee Ambrose at Sheffield Hallam University in the UK. “There shouldn’t really be a substitute for heating.”

She adds that certain ideas that sometimes pop up in film and TV, or on social media, could be a fire risk, including using candles and terracotta pots to generate warmth, or turning on a cooking device and leaving it unattended.

Low-cost hacks can help make a difference to indoor temperature, but they are no substitute for well-designed buildings and efficient, affordable heating (Credit: Getty Images)

In countries where the cost of housing, and energy, are high relative to people’s incomes, the spectre of a cold home is more likely to affect a larger number of people. And that’s when low-cost measures to improve your heating system’s performance begin to become less viable.

Antoine Rassasse lives in shared rented accommodation in London. He is currently job-seeking. “No one wants to be unemployed,” he says. In the meantime, his benefits payments only cover his main bills each month meaning he must rely on the £500 ($640) overdraft his bank offers to get by. But his flat is cold. His bedroom has single-glazing and he and the other tenants can only afford to put the heating on for a few hours each day. To help, he keeps the blinds drawn and wears multiple layers of thermals and heavy clothing.

“It’s like I am outdoors as opposed to feeling warm at home,” he says. “It’s not a great feeling at all.” Both he and Pope visit a food bank run by the charity Dads House, which has been doing an “absolutely brilliant job”, says Rassasse. “If there were no food banks, I don’t know what I would have done.”

He recalls watching a BBC TV programme last year that discussed various budget heating hacks but explains that he is wary of making too many changes to his rented accommodation. Plus, he has very little money to spend on things such as secondary glazing film. “If I had the money, obviously I would invest more,” he says.

So while these measures can help cut costs for people able to use their heating to a reasonable extent, there are still those for whom they will make little, if any difference.

And Chard helps to run Warm Home Prescription, a new service from Energy Systems Catapult and the NHS, which offers help including boiler services and payments for people in the UK to heat their homes adequately. Last winter, the service assisted more than 800 households, says Chard.

For Pope, who relies on her pension to cover her energy bills, the cost of heating remains daunting – an unfamiliar experience for her. When she was working, she never faced such difficulties. And while she is very grateful for the council’s help, Pope says a bigger response is warranted. Heating is a human right, she argues.

“More should be done for those vulnerable people, pensioners. People with disabilities. Young children,” she says. “I think more should be done for them.”