The ‘dark earth’ revealing the Amazon’s secrets

Deep within the Amazon, Mark Robinson was up to his knees in buried treasure.

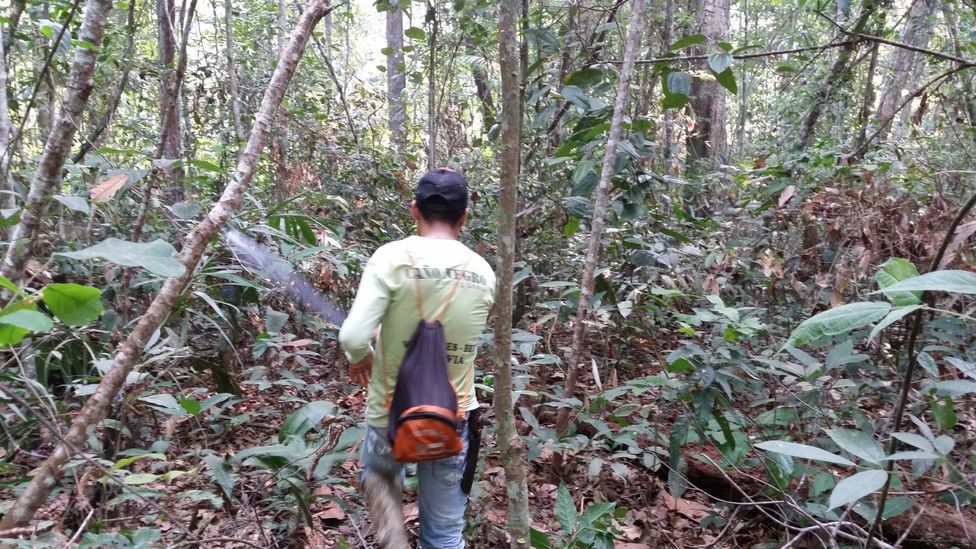

Together with an international team of scientists, Robinson was on an expedition to a remote patch of forest in Iténez, northwest Bolivia, close to the border with Brazil. Getting there had not been easy. To avoid a 10-hour boat ride, they took a hair-raising flight to the nearest village, Versalles, where the plane had to circle back over a grass runway to avoid landing on a herd of grazing animals. Then came a long trek through thick rainforest, navigating over gnarled roots and past marauding armies of ants. “It’s hot, it’s humid, you’re getting bitten constantly,” says Robinson, a senior lecturer in archaeology at the University of Exeter.

The journey, however, was worth it. The researchers had an important mission: they were searching for “Amazonian dark earth” (ADE), sometimes known as “black gold” or terra preta.

This layer of charcoal-black soil, which can be up to 3.8m (12.5ft) thick, is found in patches across the Amazon basin. It is intensely fertile – rich in decaying organic matter and nutrients essential for growing crops, such as nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus. But unlike the thin, sandy soils typical of the rainforest, this layer was not deposited naturally – it was the work of ancient humans.

This rich soil is a relic from a very different time – an era when indigenous groups formed a thriving network of settlements across this rainforest world.

In January 2024, scientists announced the rediscovery of a long-vanished “garden” city. Hidden beneath the foliage of the rainforest in Ecuador’s Upano valley was a 2,000 year-old urban centre, complete with plazas, streets and ceremonial platforms. (Read more from BBC News about the lost city found in the Amazon.) The discovery has raised questions about whether there may be other ancient settlements concealed in the Amazon. And this is where ADE comes in.

It’s thought that the garden city could only support so many people because of the region’s fertile volcanic soil. But elsewhere in the Amazon, indigenous communities relied on ADE to improve the productivity of their land. Now there’s growing interest in the lessons their methods may hold for societies today, from improving crop yields to beating climate change.

Amazonian dark earth is packed with ancient artefacts, such as pottery and fossilised seeds (Credit: Mark Robinson)

A hidden influence

Surrounded by the smells and sounds of the rainforest at Versalles, in the remoteness of the Amazon, Robinson says it would be tempting to think that you’re in a pristine wilderness. But this is not the case.

“The more we find out, [it becomes clear that] it’s not necessarily primary forest,” says Robinson. “Everywhere we look, although it seems like a really arduous trip to us, and that we’re in the most remote place, we just find evidence of past communities everywhere.”

In 2017, research revealed that domesticated trees are five times more likely to be dominant in the Amazon than non-domesticated ones – with more appearing the closer you get to ancient settlements. Though today many of the Amazon’s indigenous communities have vanished, wiped out by Western colonists and the diseases they carried, their farming practices continue to shape the rainforest.

Another crucial element of this hidden influence is ADE, which is widespread. “This is the fascinating thing – it really is pan-Amazonian, we are finding it everywhere,” says Robinson.

This precious layer contains a potent blend of inorganic material, including ash, pottery, bone and shells, together with organic matter such as food scraps, manure, and urine. It’s simultaneously a treasure trove of ancient rubbish that’s extremely exciting to archaeologists like Robinson, and a functional part of the Amazonian soil – one that continues to enrich the rainforest and allow indigenous communities to farm there today.

Amazonian dark earth has been estimated to cover 0.1%-10% of the Amazon basin (Credit: Getty Images)

“They really are a goldmine,” says Robinson. Along with fossilised seeds and ceramic artefacts dating back thousands of years, there are microscopic clues to what the rainforest may have been like thousands of years ago. One example is faecal spherulites: tiny crystals found in animal dung that hint at the kinds of animals that once roamed across the landscape – and defecated in it.

A living history

ADE first piqued the interest of Westerners in the 1870s, when several scientists independently noticed black layers of soil that contrasted with the pale or reddish kind that surrounded them. One early explorer described it as a “fine, black loam”, and noted that “strewn over it everywhere we find fragments of Indian pottery, so abundant in some places that they almost cover the ground”.

However, how ADEs were created has been something of a mystery. Scientists have questioned whether these soils were produced by accident – the product of generations of indigenous people discarding rubbish – or via an intentional process to enrich the rainforest and make its ground more suitable for farming.

In 2023, an international team of scientists weighed in. By combining an analysis of the structure and composition of ADEs with observations of, and interviews with, the indigenous community at Kuikuro – in the southeastern Amazon, in central Brazil – the researchers concluded that these layers of soil were indeed made on purpose.

While the Iténez rainforest is still inhabited today, much of the Amazon basin was depopulated after the arrival of Western colonists (Credit: Mark Robinson)

The age and distribution of these soil deposits tell the story of the rise and fall of ancient indigenous civilisations across the Amazon. While the oldest layers of these black soils are around 5,000 years old, “we see a lot more [evidence of ADEs being produced] about 4,000 years ago”, says Robinson. “There’s a lot more activity, a lot of cultural changes.”

It’s not until around 2,000 years ago, however, that they reach their peak, says Robinson. That’s the average age of the black deposits that are found over a wide area across the Amazon basin. At this point, communities were larger and formed vast networks. However, the settlements where people produced ADE were typically not on the same scale as the recently rediscovered city in Ecuador.

One reason for this could be the power of ADE itself. Within the setting of an abundant jungle habitat, enriched by indigenous people with everything they need – fruiting trees and rich soil for growing crops – Robinson believes that there may have been no need for people to turn to larger-scale agriculture. “So [it’s possible that] you don’t really need the extra hierarchical level [that tends to develop in mass settlements],” says Robinson.

But by around 500 years ago, something is clearly very wrong. “That’s when we really see it [ADE production] drop off,” says Robinson.

This is thought to reflect the aftermath of Christopher Columbus’ arrival on South American soil on 1 August 1498. When he plunged the red and gold flag of Spain into the ground on the Paria Peninsula in Venezuela, it marked the beginning of a “great dying”. It’s been estimated that 56 million indigenous people were killed across the Americas by 1600 – so many, it cooled the Earth‘s climate.

Taking inspiration from ancient methods such as Amazonian dark earth, today many companies are producing biochar as a way to lock away carbon and improve soil (Credit: Alamy)

A carbon sink

Though many of the ancient inhabitants of the Amazon have long since vanished, their legacy remains. Intriguingly, not all of the ADEs they left behind have the same make-up – in fact, they vary widely, depending on the specific ingredients used in different locations.

“But the basic mechanism for creating the soils and enriching them seems to be similar,” says Robinson. “They [indigenous people] are directly investing into the soils, starting with their own waste products,” he says. The base is mostly composed of food scraps, with added faeces and charcoal. And it is the latter that is attracting increasing attention.

It turns out that not only are ADEs extraordinarily rich in nutrients, but they are powerful carbon sinks – with up to 7.5 times more carbon within compared to the surrounding soils. As ADEs accumulate, the carbon becomes trapped underground, where it remains stable for hundreds of years – locking it away and delaying its entry into the atmosphere.

It’s not clear why the carbon within ADEs behaves this way, but scientists suspect that it has something to do with “black carbon“, also known as “biochar”. This key ingredient is made from organic material that has been turned to almost pure carbon at high temperatures, in the presence of little oxygen. The process doesn’t emit as much carbon dioxide as charcoal production, but leads to a fine, crumbly black product that has been found in ADEs across the Amazon. (Read more about biochar from the BBC).

In the village of Versalles, the indigenous Itonama community still use the fertile Amazonian dark soil to grow crops (Credit: Mark Robinson)

Now businesses are attempting to capitalise on this ancient method, in a quest to help farmers to improve their soil and combat climate change at the same time. Take Carbon Gold, a company that produces biochar for use as an organic, peat-free planting aid. Founded in 2007 by the creator of a chocolate brand, the company based its methods on Mayan cacao farmers from Belize – who have also been using biochar for millennia.

In addition to locking away carbon, “biochar improves structure, aeration, water-holding capacity, and nutrient retention” that can support healthy plant growth, says Sue Rawlings, the managing director at Carbon Gold. Today the company’s clients include organic growers, gardeners, sports stadiums, premier league football clubs, major race and golf courses and Royal Parks and gardens in the UK, she says.

For his part, Robinson thinks copying the methods of ancient indigenous people in the Amazon is going to be essential for future generations. He points to the predictions that by 2050, around half of the world’s population will live in the tropics – with large amounts of migration into tropical forests.

“Finding ways for communities to be more sustainable in them, I think it’s essential,” he says. “And there are things we can learn from the past about this. I think we’re just on the cusp of understanding this.”